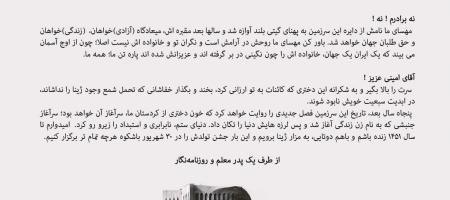

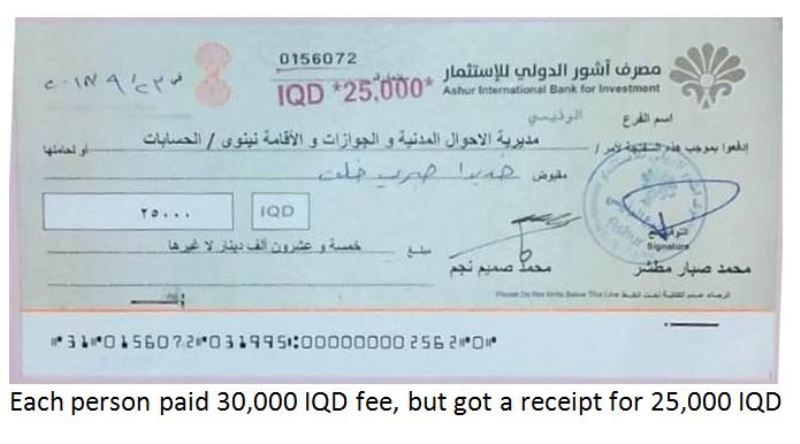

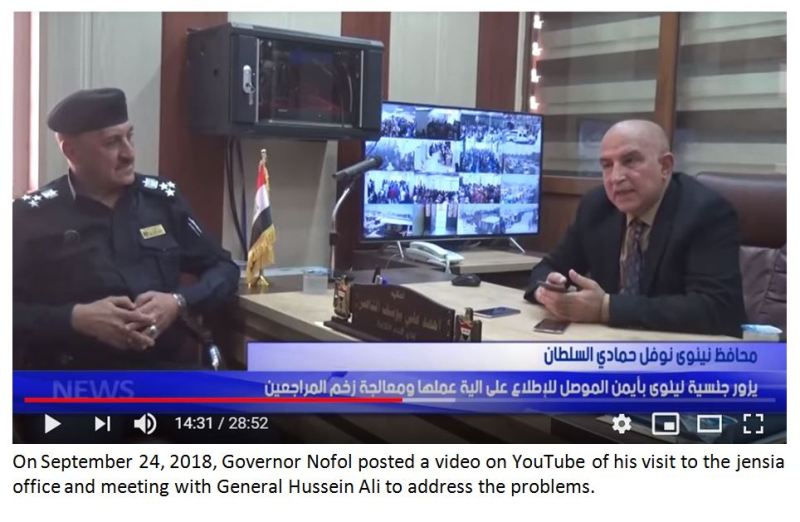

On Sunday, September 23, an Ezidi family from Shingal was denied fingerprinting processing for passports after having paid their government fees of 30,000 dinar ($25 USD) per passport plus 5,000 dinar for the computerized application form at the Faisilia, Mosul, office in Nineveh province, Iraq. The receipt for paying the 30,000 government fee is stamped for only 25,000 IQD. (In the Duhok passport office, the bank receipt for paying 29,000 IQD is also stamped as 25,000 IQD.)

No explanation or receipt is given for this hidden 4,000 or 5,000 dinars. Can this overcharging without an accurate receipt be considered anything other than corruption?

The denial of fingerprinting was after Dr. Amy L. Beam, an American activist for displaced Ezidis, had reached an agreement in September 2018 with Dr. Khalid Awnee Hataub, the Mosul passport director, to send up to twenty Ezidis every Thursday for assistance in applying for passports without appointments or waiting in long lines.

According to Dr. Khalid, no appointments are necessary for any Nineveh resident, so this was a courtesy for Beam and her Ezidi families, not a requirement for applying. The families must travel three hours in each direction from either Shingal or Zakho. It is important they complete the application process in one day because of the cost and fear of staying overnight in Mosul which was the former headquarters of Daesh.

The displaced family of nine of Khudeeda (Kamal) Sabri Khalaf, after paying their fees, was told that for fast processing, they had to pay an additional 250,000 dinar ($209 USD) per person. Khudeeda told the officer they did not need fast processing and did not have the money. They would wait the normal ten days to get their passports made.

Mosul passport employee, Ahmad Hussam, answered, "In this office we give passports only by money."

Khudeeda asked Ahmad, "What is the solution for us?"

Ahmad answered, "You have to pay the money or take your family home." The family was denied fingerprinting processing after spending 400,000 dinar ($335 USD) in government fees, files, and taxi fare. When Khudeeda asked for an appointment, Ahmad Hussam stated, "We do not give appointments."

Beam states that in a heated phone call with Ahmad Hussam, Ahmad said he would not honor her lists of names without a letter of authorization for each family from General Najim al Jubouri, chief commander for Nineveh province operations. Ahmad stated, "We work with the government only, not NGOs. I will not break the law."

"What law is that?" Beam demanded. "There are no appointments necessary in Mosul, and the family has paid their government fees to be fingerprinted and processed. In fact, any family from Nineveh should be able to go any day of the week to Mosul to apply for passports without appointments."

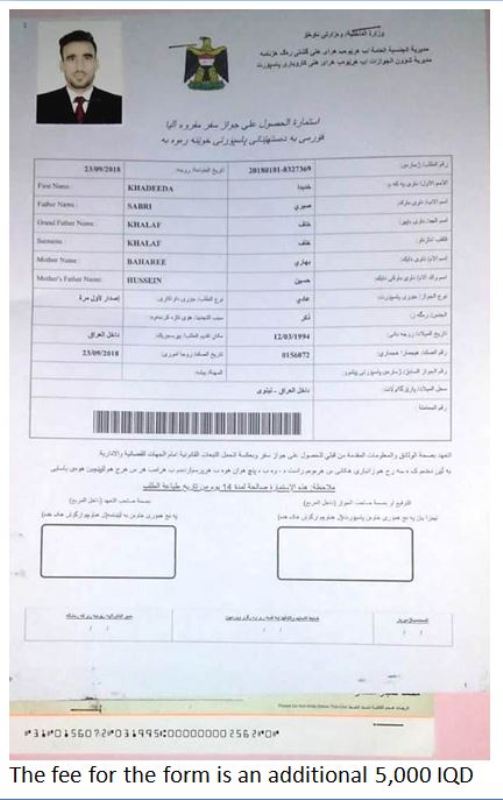

Beam went directly to appeal to Shingal mayor Mahama Khalil in Duhok. He phoned General Hussein who was out of the passport building in a meeting with Mosul Governor Nofol. General Yunis was the director of the passport, jensia, and hawea offices in Nineveh. He retired in mid-September 2018 and was replaced with General Hussein Ali.

General Hussein's assistant took the names of each person requiring fingerprinting and directed Ahmad Hussam and other staff to fingerprint them. In spite of two hours of repeated calling and directives, the Mosul staff refused to fingerprint Khudeeda's family. They also refused to process the mother and grandmother for their jensias after General Hussein had instructed his staff that same morning to process their jensia applications.

Beam states, "I did not dream it that in a meeting two weeks ago Dr. Khalid Awnee, Mosul passport director, authorized me to bring up to twenty Ezidis per week for personal assistance with passport processing without any further letters of authorization from General Najim or anyone else. General Hussein Ali, director for jensias, stated in that meeting that he knew me for three years and urged Dr. Khalid to help my humanitarian work by removing burdensome paperwork requirements such as weekly letters of authorization from General Najim. Dr. Khalid agreed to General Hussein's recommendation and instructed me to send the lists of names by WhatsApp to his staff member, Ahmad Hussam, who speaks English and was in the meeting. I did this, and then Ahmad refused to fingerprint the family unless they paid more money or I sent a letter from General Najim."

Beam continued, "General Najim is a military commander who must deal with issues of policy and strategy for all of Nineveh security. It is inappropriate to abuse his time by asking him to approve weekly lists of names of people who need passports. This is a bureaucratic matter, not a military security matter."

In a follow-up phone call with Beam, Mosul governor Nofol confirmed there are two methods for getting passports. One is normal processing for 30,000 dinar ($25 USD) and the other is expedited processing for 250,000 dinar ($209 USD). Governor Nofol told Beam to refer the matter to General Najim.

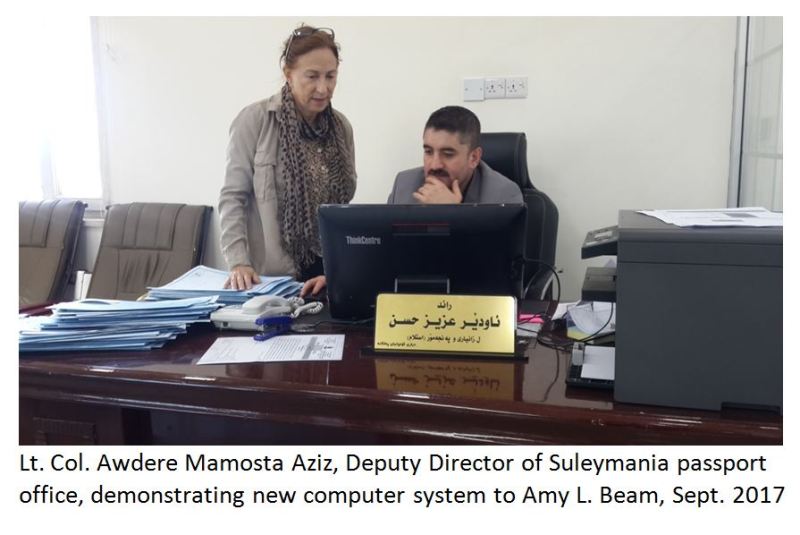

The costs for normal and expedited passport processing were also confirmed by General Dildar Nuri, the Duhok passport director; Lt. Col. Awdere Mamosta Aziz, the deputy director of the Suleymania passport office; and General Hussein Ali, the director of Nineveh jensia offices. General Hussein had directed his staff to process the family for passports before leaving for his meeting.

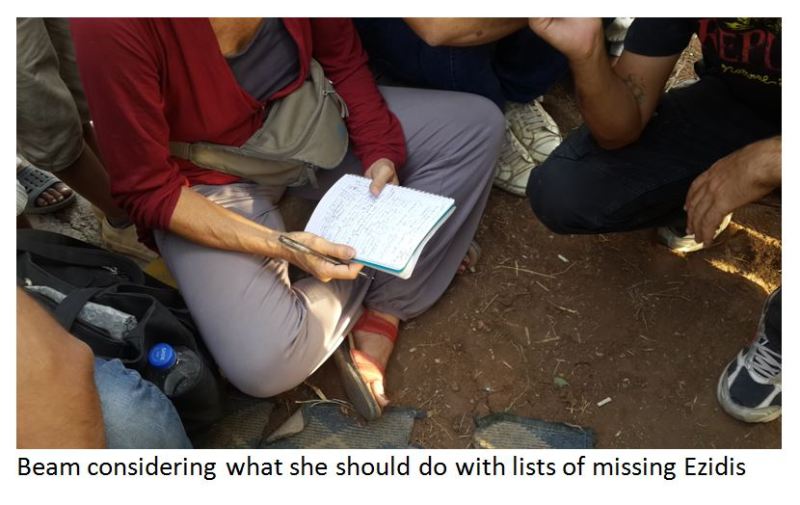

Beam first became involved in assisting Ezidis when she was living in Sirnak, southeastern Turkey, when Daesh (ISIS) attacked Ezidis in their homeland of Shingal, northern Iraq. The entire population of 300,000 Ezidis was displaced from Shingal on August 3, 2014. Twenty-five thousand Ezidis did not stop fleeing until they crossed the mountain border from Iraq into Turkey. Beam began making her first lists of names of missing and has since filled several dozen notebooks with lists of names of missing, dead, and survivors who have returned.

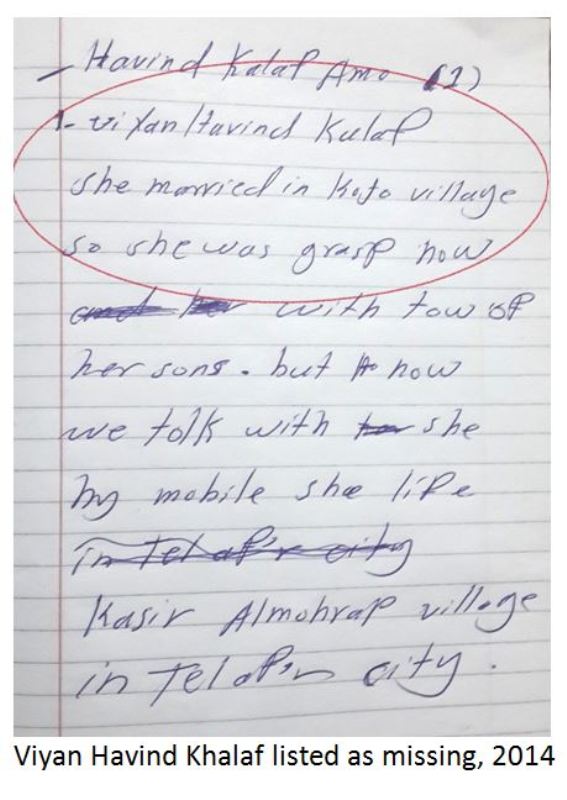

In 2015, Beam moved to Duhok, Kurdistan, where she met her first survivor from Kocho, the village where Daesh killed all the men and abducted all the women and children on August 15, 2014. Viyan Havind escaped from Daesh after being held prisoner for eight months in Tal Afar, Iraq, with her two toddlers. Her husband, Basman, is missing, presumed dead.

"When I asked Viyan what she most needed three days after returning to safety in Kurdistan, northern Iraq," says Beam, "she told me she did not need money, a house, or car because she was safe with her family in the camp. 'I need only one thing' she said. 'I need to leave Iraq forever with my children.'"

"Viyan's plea launched me on my passport project," explained Beam. "While other people discussed the need for psychological therapy for the rape survivors, I understood that the healing therapy they most needed was simply to emigrate to a safe country with their children."

Since 2015, Beam estimates she and one staff person have gotten more than 700 passports for survivors with the help of private donations. Most of them are now in Germany. Australia is now taking families of Ezidi survivors. Requests to Beam have escalated. Her donation money is exhausted.

The waiting time for an appointment in the Duhok passport office grew from three months in 2015 to the current two-and-a-half-year wait for persons displaced from Shingal (IDPs or "internally displaced persons"). There is no appointment necessary for Duhok residents.

Under a special arrangement between the Duhok passport office and Baghdad central government, Duhok now processes 250 passport applications weekly for displaced persons from Shingal in the Nineveh province which falls under the Mosul jurisdiction.

In 2015, more than one million Iraqis were internally displaced by Daesh. Under chaotic conditions, the passport offices raced to expand their facilities and staff to accommodate the demand for documents.

In 2015 and 2016, the illegal bribes to obtain documents from Baghdad without waiting were $50 for the hawia ID card, $50 for the application form for the national identity card (jensia), $250 for a jensia, and $500 for a passport.

An NGO director in Baghdad who wishes to remain anonymous, stated, "Under Saddam Hussein there was very little corruption, because Saddam was severe with punishments. He would execute people for corruption. Now, corruption is not even hidden below the table. It is in plain sight. Many consider it acceptable to demand money to do their government job. Everyone in Iraq knows you cannot get anything from the government without paying 'whasta,' a nice way to say a 'bribe.' Too many people are involved in this system of corruption which has destroyed our government, our country, and the ethics of Iraqi citizens."

In 2015, Dr. Beam met with the passport directors in both Duhok and Suleymania to reach agreements to take Ezidis for passports without appointments or bribes or "whasta". She and her team take survivors and their families, families with missing family members, and interpreters who once worked for the US Army and are applying for immigration to the United States under a special program.

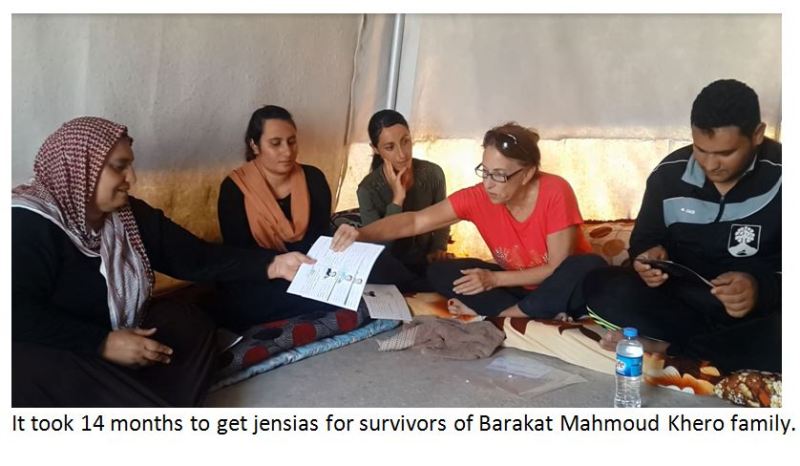

Dr. Beam and her staff must take the survivors to five or six offices at least two times to get their police report, court documents, hawia, jensia, green residency card, and passport. In 2017, the staff corruption for obtaining jensias or national identity cards was so severe that it took Beam 14 months to legally get the jensias of the Barakat Mahmoud Khero family whose father and brother had been killed and the three sisters sexually abused by Daesh for more than three years.

In January 2018, Beam submitted a report on corruption to a Mosul Council member. This report was studied internally. Several of her recommendations were implemented. One was to distribute application forms for haweas and jensias to all the IDP camps in Kurdistan in order to stop the corruption of restricting access to the forms by illegally selling them.

Mahama Khalil, mayor of Shingal with his office and staff headquartered in Duhok, began delivering hawea forms to 16 IDP camps on a rotational basis. The hawea is free in the camps. At the hawea offices, it costs 1,000 dinar or less than $1 dollar. The jensia costs 2,000 dinar.

Unfortunately, Qadia camp, near Zakho, Kurdistan, has not had any hawea forms delivered for three months. So returning survivors must travel six hours to Snoni, Shingal, to get their hawea ID card. No jensia forms are delivered to the camps.

The other of Beam's recommendations was to implement a fee for obtaining expedited passports. Beam states that in the United States, fees for expediting processing of nearly every kind of government document is available for persons who do not wish to wait. The fees are significantly high so as to discourage their use except for emergency situations.

In September 2017, the Baghdad central government installed a new computerized system in all passport offices in Iraq, including Kurdistan. This streamlined and standardized the procedures in all offices.

The procedure is to first make a file for each application, have the file inspected and get signed approval, then pay the government fee. After the fee is paid, a receipt is given. The applicant shows this receipt to another employee who assigns a number in the computer system. The applicant sits and waits in a room until his or her number is shown on a lighted overhead panel.

The person then goes to a window to have an electronic thumb print and eye scan taken. After fingerprinting, he or she is given a receipt to pick up the passport on a later date when it is ready. The normal waiting time in Mosul is ten days and in Duhok it is now as much as three months. The Duhok office has a backlog of 7,000 applications waiting to be processed in Baghdad.

In 2018, the Baghdad government implemented a fee of 250,000 dinar ($209 USD) for getting a passport issued in 48 hours. This fee and fast processing is available in all passport offices.

Unfortunately, staff in Mosul passport office have corrupted this legitimate fee for fast processing by telling the Ezidi family of Khudeeda Sabri Khalaf that it is required and there is no other way to obtain their passports. How many other families have been turned away with the same lie or paid unnecessary fees?

Might one infer that the family's two receipts for 25,000 dinar and 5,000 dinar for each person would provide the necessary receipt numbers for entering into the government computer system, while the 250,000 dinar extortion would go directly into an employees' pocket? How else can this "requirement" be explained except by calling it corruption?

The family of Khudeeda Sabri Khalaf is still awaiting an explanation for why they were refused fingerprinting after paying their government fees.

Dr. Amy L. Beam defends the integrity of the previous Duhok passport director, Nawzad Majid Suleiman, and the current passport director, General Dildar Nuri, as well as the Suleymania Deputy Director who was consulted, Lt. Col. Awdere Mamosta Aziz. She insists they are not involved in corruption. The directors each firmly stated they would prosecute in court anyone known to be taking bribes for issuing passports.

"These directors have given me great support in getting passports for survivors of Daesh captivity, and I support them completely," Beam stated.

"I call on Dr. Khalid Awnee in the Mosul passport office to fingerprint the family of Khudeeda Sabri Khalaf and issue their passports without delay. I also call on him to post visible signs in the Mosul office stating the normal passport fees without appointments (25,000 fee plus 5,000 for the form) in order to eliminate corruption. And lastly, I urge the government fee of 25,000 dinar as stated on the receipt to be collected without collecting an additional 5,000 dinar that is unaccounted for."

Dr. Amy L. Beam is the author of The Last Yezidi Genocide. She is well-known by Ezidis world-wide as a voice for their plight and demands. She continues to advocate for mass migration for displaced Ezidis who are suffering in camps with no hope of returning to Shingal, not just those who were captured and abused.